Central Region States Seeking to Boost Home Care Options

Stan Morton, 84, admits being skeptical at first when an occupational therapist visited his Englewood, Colorado, apartment this year.

“People in my stage of life tend to hear, ‘you need to do this, you need to do that’ pretty much all the time,” says the retired government employee. “Everybody’s got an opinion.”

But the therapist didn’t tell him what to do. Instead, she asked him what challenges he faced and worked on solutions to help make it easier and safer to continue living independently. Relying on supplemental oxygen 24 hours a day, Morton had been pulling a 50-foot tube through his apartment. After talking with the therapist, he began rolling up the tubing in his left hand to avoid tripping on it.

Letting older adults like Morton set their own goals is a key part of what’s known as the CAPABLE program, a unique model for delivering short-term, home-based services to help older adults overcome challenges with daily activities and remain living at home.

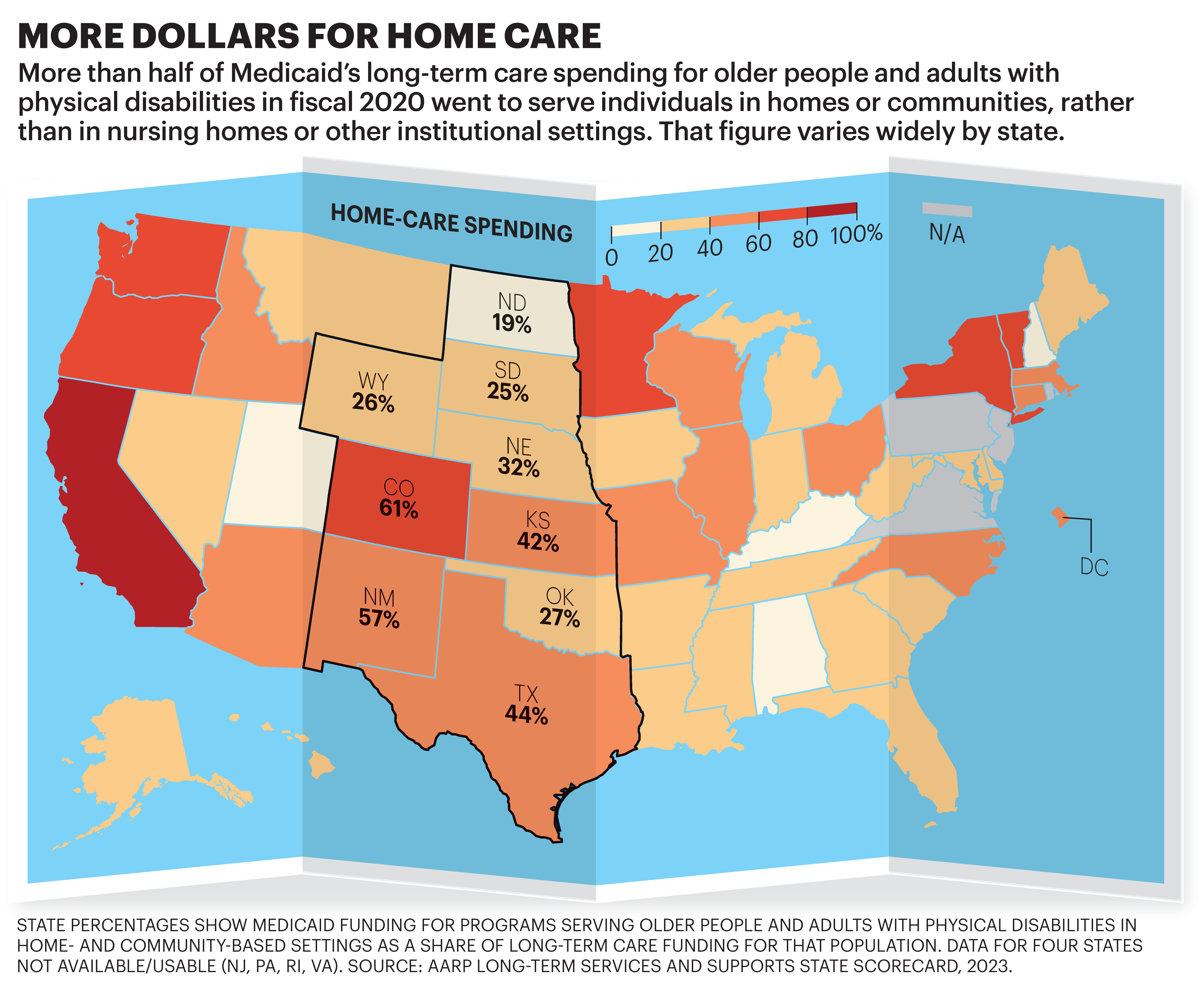

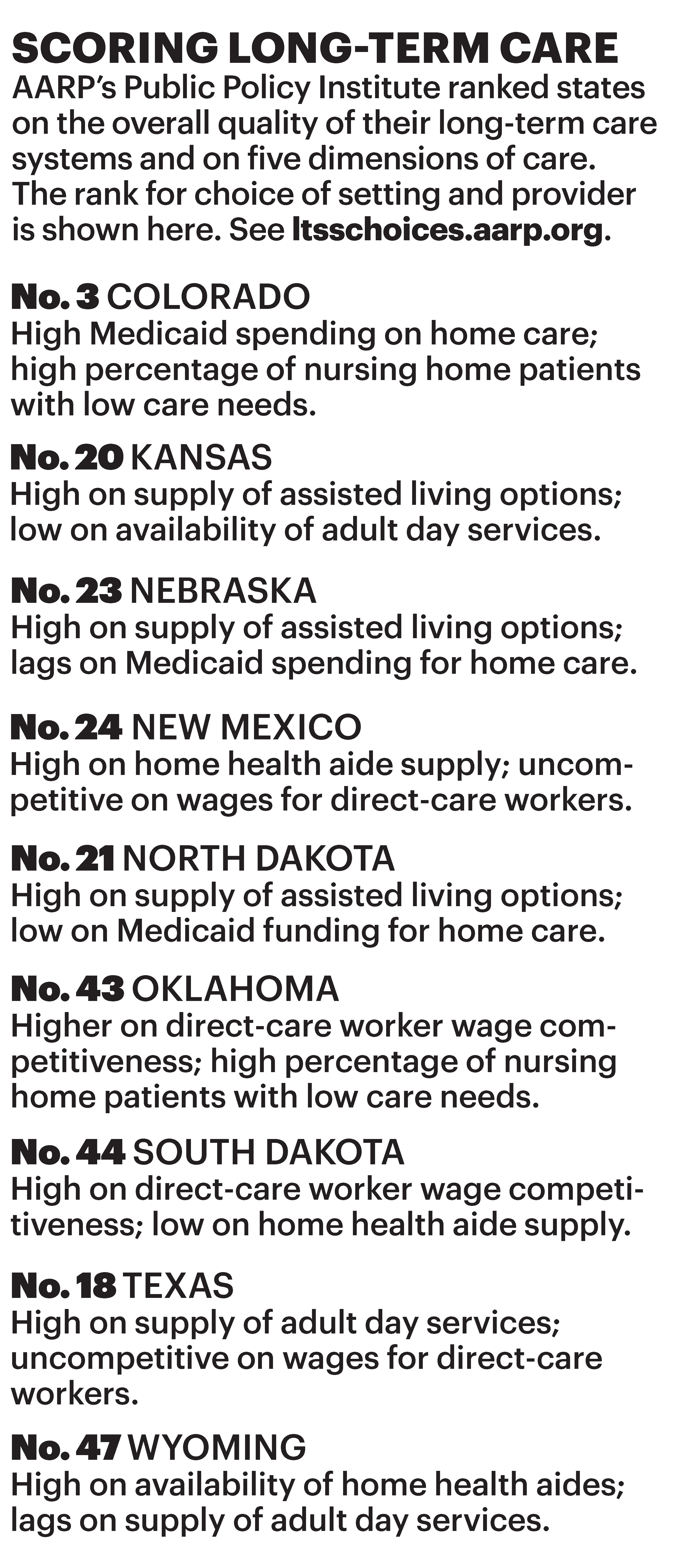

The program is one of the innovative ways that states across the country are working to provide more long-term care services in homes and communities instead of in nursing homes and other institutional settings, according to AARP’s latest Long-Term Services and Supports State Scorecard. AARP used 50 spending, quality and access indicators to rank each state’s long-term care system.

For the first time since AARP began publishing the Scorecard in 2011, more than half of Medicaid long-term care dollars nationwide for older adults and people with physical disabilities went to home- and community-based services instead of institutions. In the Central region, Colorado, New Mexico, Kansas and Texas rank among the top 25 states for HCBS spending.

EXPLORE: AARP Long-Term Care Scorecard

“This is a big deal,” says Susan Reinhard, senior vice president of the AARP Public Policy Institute, which published the Scorecard in September. “We are seeing a breaking point.”

CAPABLE, which stands for Community Aging in Place—Advancing Better Living for Elders, is currently offered at sites in 22 states.

Over the course of four to five months, each person in the program receives multiple visits by an occupational therapist and a nurse, as well as minor home repairs and modifications by a handyperson. Studies show participants are less depressed, have improved confidence about completing tasks without falling and experience reduced limitations in their daily lives. For Morton, the program added a railing to prevent him from slipping out of bed, an extra handle in the bathroom to help him get out of the tub and a medication dispenser with an alarm to remind him when to take his pills.

The program also saves money by helping to avoid hospital and nursing home stays. Last year, Colorado invested $2.3 million to expand CAPABLE.

A WIDENING GAP

Demand for home- and community-based services, through programs like CAPABLE, has increased—fueled in part by the COVID-19 pandemic that took a horrific toll on nursing home residents. Polls have shown that most older Americans want to age in place.

But America’s rapidly aging population, combined with persistent shortages in the long-term care workforce, means the chasm between the availability of and access to HCBS care is poised to widen.

“We’re going to see a dramatic increase in the 80-plus and 85-plus population” as boomers get older, says Robert Applebaum, a senior research scholar at Miami University’s Scripps Gerontology Center in Ohio.

States are working to address the issue on multiple fronts, including increasing support for family caregivers.

In South Dakota, lawmakers recently allocated $2 million to expand adult day programs in the state for individuals living with dementia, says Erik Nelson, AARP South Dakota advocacy director. The centers provide caregivers with a break but also give older adults a chance to participate in activities that improve their quality of life, he says.

In Oklahoma, lawmakers this year passed a bill creating a tax credit for family caregivers to help offset the out-of-pocket costs that arise when caregiving.

Another way states are improving HCBS: giving more older adults control over their care, allowing them to choose what services they receive and to hire their own workers.

Nationwide, these “self-directed” care programs increased enrollment by 10 percent or more in 35 states, according to the Scorecard. In the Central region, six states—Colorado, New Mexico, Kansas, Texas, South Dakota and Oklahoma—have improved their performance in enrolling people in such initiatives in recent years, the Scorecard shows.

In Colorado, participants can hire a family member, neighbor or friend to be a paid provider as long as they meet basic qualifications, says Bonnie Silva, director of the state’s Office of Community Living. The practice not only allows an individual to get help from someone they know and trust but also helps family caregivers, who are often already providing unpaid care.

WORKFORCE CHALLENGES

One of the biggest challenges states face in expanding HCBS is the shortage of direct-care workers, such as home health aides.

The Scorecard shows that nationwide, wages for direct-care workers are lower than for jobs with similar or lower entry requirements. In most states, the shortfall is more than $5,000 annually. In 2021, the median pay for direct-care workers was around $30,000.

Low wages are compounded by the fact that some direct-care workers may receive little training and few or no benefits for jobs that are physically and mentally demanding.

Colorado allocated more than half of the $522 million it received in federal COVID-19 relief funds aimed at enhancing HCBS to addressing the workforce challenge, Silva says. Some of that money went to increase the base wage for direct-care workers to at least $15.75 per hour. Before, worker pay averaged $12.41 per hour, Silva says.

States are raising wages and increasing benefits, but demand for HCBS is only growing, says Carrie Blakeway Amero, the AARP Public Policy Institute’s director of long-term services and supports. “They need to keep doing it and double their efforts,” she says.

Michelle Crouch is a North Carolina-based writer who has covered health issues for Reader’s Digest, The Washington Post and other publications. She has written for the Bulletin for more than a decade.

More on Home Care

- Care Companions: A Watchful Eye and Willing Ear for Older Adults

- Find the Right Home Aide for Your Loved One

- AARP Survey: 8 in 10 Older Adults Want to Age at Home